“Winning the Global Impact Award at this year’s Alliance Awards for our Solar Energy Transitions (SET): Inclusive e-cooking in sub-Saharan Africa project was a genuine privilege, not least because of the strength of the other shortlisted nominees. Each project was delivering excellent examples of challenge-led research that had both global relevance and local impact.

Funded by Innovate UK through the Energy Catalyst programme our own intervention centred on co-creating solar e-cooking systems with communities in Rwanda who had no prior access to electricity. The immediate impacts of the systems were clear: reduced smoke, significant time savings in firewood collection, and cleaner, safer cooking practices (fig. 1). These outcomes mattered in everyday life, especially for women and children.

Yet the greater significance of the project lies less in these outputs and more in the Designing for Transitions (DoT) model that underpinned this work. Energy transitions are rarely linear: they emerge through the entanglement of technical systems and social practices to reveal how communities and innovations co-evolve. Understanding this interplay provides insights into how we can rapidly scale-up new sustainable and successful energy services and products.

Figure 1: Households were given an induction hob and pressure cooker powered by solar-battery technology

1. Building capacity through co-created transitions

Rapid adoption was possible because we were not just installing a device but building capacity for transition. Households that had never cooked with electricity became active resourceful users making informed decisions about solar energy management.

That shift did not happen by chance. By approaching co-creation not as a set of workshops but as a capacity-building programme, it brought households, policymakers, and solar companies into the same process (fig. 2). This allowed us to not only gain direct insight into user practices and system performance that benefited the sector, but the introduction of participatory methods, gamification, and real-time feedback turned the workshops into spaces of shared discovery. For example, a boiling water race introduced households to the efficiency of the induction hob and pressure cooker, while a ‘Price Is Right’ activity explored perceptions of affordability by asking participants how much they would sell the system for rather than what they would pay to buy it. This inversion proved more revealing, highlighting how much households valued the system in relation to its usefulness, reliability, and place within everyday life.

This alignment meant that technical design of the system, household skills, and policy priorities could be explored together. As a result, everyday practices were not just translated into evidence for policy and markets, they actively rewrote the terms of transition, demonstrating that durable energy futures are only possible when households are recognised as co-designers of systems, markets, and policy.

Figure 2: Households, policymakers, and solar companies came together at the Komera Women’s Business Hub, Kayonza District, Rwanda, for four different day events during the SET project.

2. Accelerating transitions: Rethinking the ‘energy ladder’

Conventional models assume that households move step by step up the ‘energy ladder’, from wood to charcoal to gas, then to clean energy, such as electricity. Our study showed otherwise.

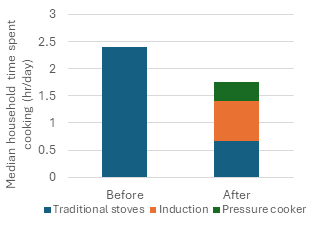

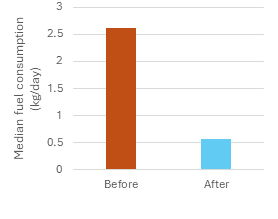

Families with no prior experience of electricity adopted e-cooking almost immediately. Within hours of being deployed, they were confidently managing the e-cooking systems, leapfrogging entire stages of the ladder (reducing the time spent using traditional cookstoves and consumption of polluting fuels by over 70% — see fig. 3).

This acceleration matters, it shows that waiting for gradual progression is not inevitable, and that with the right design, underserved and energy-poor households can bypass linear trajectories and redefine what transition pathways look like in practice. The impact is that climate, economic and health benefits from reducing the use of highly polluting fuels can be realised straight away.

Figure 3: The time spent cooking and fuel consumption before (October 2023 – March 2024) and after (April 2024– August 2024) having access to a solar e-cooker.

3. Gendered transitions in domestic labour

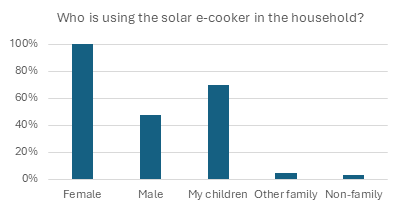

Clean cooking interventions often risk reinforcing gender essentialisms by positioning cooking as the sole responsibility of women. Globally, women and girls already shoulder most of the domestic cooking responsibilities, and in the households we engaged with, this was no different: all households described it as women’s work. Through Designing for Transitions, we embedded a gender-critical lens that involved all members of the household in recognising the scale and impact of traditional cooking on different groups. This approach created a means of unsettling assumptions about whose labour is valued, who can participate in technological change, and how new technologies can be a tool to renegotiate fairer domestic roles and division of labour.

An unexpected outcome reported by women was the willing engagement of men and children in using the e-cooker, albeit mostly for reheating or boiling water (fig. 4).

While the long-term sustainability of this shift remains to be seen, energy transition in this sense was more about household negotiations on how the benefits and burdens of new technologies could be shared more equitably. By making space for households to actively explore how to reshape responsibilities, this powerful indication of how the DoT, deliberately designed to explore ways of disrupting gender roles, can support wider positive change for all.

Figure 4: Users engaging in e-cooking as reported through monthly surveys by the households (Apr-Aug 2024)

What happened in Rwanda is more than a local success: it shows that when households, companies, and policymakers co-create, transitions accelerate, roles shift, and capacity grows.

Designing for Transitions is transferable to other renewable energy interventions, because it is an eco-system for underserved households that fosters a sustainable future where practice, policy, and markets can evolve together.”

Data availability

Surveys, e-cooker system and kitchen sensor datasets relating to this article can be found at an open-source online data repository hosted at Zenodo.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Innovate UK through the Energy Catalyst programme (Grant No. 10044025) as part of the Solar Energy Transitions (SET): Inclusive e-Cooking in sub-Saharan Africa Project.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the project delivery partners — Coventry University, Mesh Power, and Rwanda Energy Group — as well as the significant technical input provided by Climate Solutions Consulting.

We further extend our appreciation to Kayonza District and its leadership, REG community surveyors and translators, Mesh Power’s technical support team, and the Coventry University Africa Hub for their essential support in the implementation of this work. Finally, we express our profound gratitude to all participating households, whose engagement was indispensable to the success of the project.